When England’s players were fined 20% of their match fee after the fifth Ashes Test at The Oval for a slow over rate, it caused barely a ripple. The Ashes had been won so who cared? The lack of attention suggests an acceptance that slow over rates are now just part of the game.

When England’s players were fined 20% of their match fee after the fifth Ashes Test at The Oval for a slow over rate, it caused barely a ripple. The Ashes had been won so who cared? The lack of attention suggests an acceptance that slow over rates are now just part of the game.

Move forward to Abu Dhabi in November, where England were denied a victory in part because of a slow over rate throughout the game, and the issue has been put in to far greater focus. The allotted 90 overs were not completed on any of the five days of the Test and 17.3 overs were lost in all. England would have won the game if some of those overs had been bowled and, more importantly, the paying spectator wouldn’t have been short changed.

Temperatures were searingly hot and light fades fast in the Emirates so there is some mitigation, but this is not a problem confined to certain teams or conditions; it is a problem that blights every Test match around the world. In the 1950s, Test cricket was regularly conducted at 20 overs an hour, and in country cricket sometimes even quicker than that. In modern day Test matches, the over rate is consistently around 13 overs per hour.

The minimum over rate stipulated for Test cricket is 15 overs per hour during a six hour day, with an extra half hour available if overs have not been bowled. The rate is allowed to fall to 13 overs an hour because of allowances in the ICC’s playing conditions for fielding sides who do not comply. Some of these are reasonable: time taken out of the game due to injury for example, but others less so. An allowance for ‘all other circumstances that are beyond the control of the fielding side’ strikes this observer as providing too much scope to plead innocence.

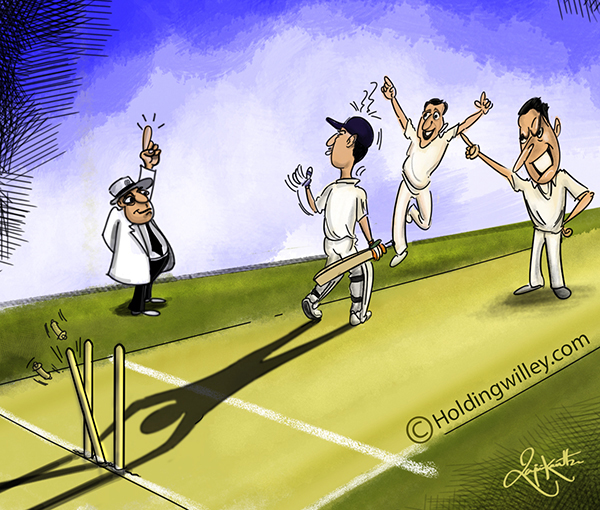

Watch a day’s Test cricket and you will see a myriad of delays which take the odd minute here or two minutes there but when combined lead to three or four overs missed each day. Most of the delays would not have occurred in the 1950s simply because the modern game is now so professionalised.

“

The twelfth man is constantly providing drinks to players so they can hit their sports science inspired fluid intake requirements. How to conserve energy is now also science, bowlers wasting not a drop on the way back to their mark. Shane Watson’s walk back takes so long you never think he will make it. There are mental as well as physical strategies to improve performance. Batsmen have pre-delivery routines to improve concentration and focus, Jonathan Trott’s marking and scratching before each delivery an extreme and infuriating example.

”

Analysis of opponents is a full time-job and teams have numerous specific fields for each opposing batsman, requiring detailed implementation by the captain. In days passed, two slips and a gully may have remained in place for the whole day. Australia’s now retired captain Michael Clarke often changed the field every few balls.

As players and teams have been professionalised, so too has the officiating. The Decision Review System (DRS) helps to avoid umpiring errors, but using DRS takes take time out of the game, even more so as sides get back their two reviews after 80 overs. Reviews made in hope rather than certainty are commonplace, the captain knowing that two reviews will be returned soon enough.

All of these things take time out of the game, but are not deliberate time-wasting tactics. For the modern cricketer, more is at stake now than ever before – a good career with IPL contracts and the like can make players millionaires – and careers are short with earning potential dependent on performance. Why wouldn’t they do everything possible to perform at their optimum? Regular hydration and conserving energy can improve performance, so they do it.

It is an understandable argument, but 20 overs an hour didn’t stop Donald Bradman from averaging almost a hundred or Frank Tyson from bowling like the wind.

The success of Twenty20 cricket, where the paying public can see a result in three hours, means Test cricket has to keep relevant and provide spectators with value for money. England fans who had travelled out to the UAE should have been celebrating a rare England away victory instead of ended up as a draw. Without a crowd, you can have all the pre-delivery routines you want, nobody will be watching.

There are punishments in place but fines or bans for captains have proved ineffective. Top players are handsomely rewarded, so the threat of a fine is of limited value, and banning the captain is a rarely used penalty in Test cricket, although more prevalent in the one-day game. Pakistan’s Misbah-ul-Haq slowed the game down on the last day in Abu Dhabi, but such is the pressure for success in the modern game that he would likely have done the same, even if facing a ban, to avoid defeat.

The remedy? Sanctions need to be more relevant and there needs to be a stronger will among officials – players will not churn out 20 overs an hour without a prod. A five or ten run penalty for each over behind the necessary rate, added to the opposition’s score at the end of the day’s play, is something that might focus minds. A target of 17 overs an hour might increase the rate and a real drive by the umpires to speed things up would also be welcome.

With day/night Test cricket being tried out in Australia last month, radical solutions to the issue of Test cricket’s sustainability are being looked at. But combating slow over rates should be an easy fix. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.